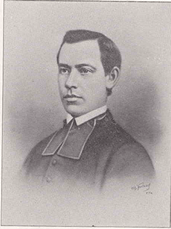

Irish Famine Orphan: Robert Walsh

A decent couple had sailed in one of the ships, bringing with them two girls and a boy, the elder of the former being about thirteen, the boy not more than seven or eight. The father died first, the mother next. As the affrighted children knelt by their dying mother, the poor woman, strong in her faith, with her last accents confided her helpless offspring to 'the protection of God and His Blessed Mother,' and told them to have confidence in the Father of the widow and the orphan. Lovingly did the cold hand linger on the head of her boy, as, with expiring energy, she invoked a blessing upon him and his weeping sisters. Thus the pious mother died in the fever-shed of Grosse Isle. The children were taken care of, and sent to the same district, so as not to be separated from each other. The boy was received into the home of a French Canadian; his sisters were adopted by another family in the neighbourhood. For two weeks the boy never uttered a word, never smiled, never appeared conscious of the presence of those around him, or of the attention lavished on him by his generous protectors, who had almost come to believe that they had adopted a little mute, or that he had momentarily lost the power of speech through fright or starvation. But at the end of the fortnight he relieved them of their fears by uttering some words of, to them, an unknown language; and from that moment the spell, wrought, as it were, by the cold hand of his dying mother, passed from the spirit of the boy, and he thenceforth clung with the fondness of youth to his second parents. The Irish orphan soon spoke the language of his new home, though he never lost the memory of the fever-sheds and the awful death-bed, or of his weeping sisters, and the last words spoken by the faithful Christian woman who commended him to the protection of God and His Blessed Mother. He grew up a youth of extraordinary promise, and was received into the college of Nicolet, then in the diocese of Quebec, where he graduated with the greatest honours. His vocation being for the Church, he became a priest; and it was in 1865 that, as a deacon, he entered the College of St. Michael, near Toronto, to learn the language of his parents, of which he had lost all remembrance. He is now one of the most distinguished professors of the college in which he was educated; and, in order to pay back the debt incurred by his support and education, he does not accept more than a small stipend for his services. Of his Irish name, which he was able to retain, he is very proud; and though his tongue is more that of a French Canadian, his feelings and sympathies are with the people and the country of his birth. The prayers of the dying mother were indeed heard; for the elder of the girls was married by the gentleman who received them both into his house, and the younger is in a convent.

As an Irish famine orphan who became a member of the clergy, Robert Walsh left extensive records at Archives du Séminaire de Nicolet. One of the most poignant of these is a letter that he wrote both in English and in French to a bishop in Ireland in 1857, asking him for help in tracing his relatives and a little sister who did not make the voyage to Canada with them ten years earlier, but was left behind in Ireland. In his own words:

Reverend Sir,

...

In the horrendous emigration of 1847, my father, David Walsh, and my mother, Anora O’Donnell resolved to go with their family to New York where they had relatives. They had five children; but they left in Ireland with relatives or acquaintances a little girl, aged roughly five to six months, if I remember well. She could have been more or less, for I then was but seven years old and had experienced a long voyage so my misfortunes made me lose the exact memory of these things. My oldest sister was ten and called Mary, the youngest was eight and is called Anny; I had a younger brother called Patrick; I think he was only four years old.

We all arrived in Quebec on the St. Lawrence at the end of June or beginning of July 1847 [sic 1848]. There, my father, my mother, and my brother Patrick died. They were sick of the typhus which caused so much devastation in this year in Canada. We were three, my two sisters and me, without any support in a foreign country. Providence alone remained for us. Also, He did not forsake us. We were helped by a Catholic priest who was very good to us and ensured that we were adopted into a French-Canadian family and provided with an excellent education. My two sisters are teaching in a good school and receive sufficient wages for their needs. As for me, I am now studying in a Canadian college and I will finish my studies within two years. Also, I am not more than ten or fifteen miles distant from my sisters so that we can write easily and even see each other sometimes, especially during the two months of holidays we are given in the fine season of summer that we spend together.

The purpose of the present letter is then to inform your greatness the particular account of these things in order that you can be moved to take an interest in the fate of these three orphans, to search and discover if they still have any relations left in Ireland. For a decade we have learned nothing of them, and we are like those who have no relatives or acquaintances. I hope that you will do all that is in your power to find some people, if any, who will be dear to us. We were of Kilkenny, if I am right, and there must still be some of our relations there.

My father was the intendant of the lord Montgomery who lived very near Kilkenny then I believe. It was he who conveyed labourers in the lord’s service. I was then an infant and I remember that I would go sometimes with my mother and sisters and the lord to a magnificent orchard near his estate. How I love to recall these memories which are for me like a fair dream! Yes, I had a father, a mother, and now they are no more. If only I learned one day that we have relations who think of us, who know the details of our misfortune, and who would write to me, then I would be a little comforted; for they also have learned nothing of us for ten years. They would be glad to know something of us. My sister, my dear sister, if she exists, when she would learn that she has a brother and sisters in Canada who are thinking of her she would write to them, although she does not know them! Oh! how much these words would mean in our hearts! We will see then we are not alone in the world, and it is this thought that will give us courage to endure our separation here.

I hope that your Lordship will take into consideration my questions and that you will do all that charity permits on this occasion. I will be in your debt if you may discover some of my relations and let me know of them soon.

I still have something else to ask of you if you will permit me, on what I have said lately. It is that, as I said, my father was a steward of Lord Montgomery, and also that his Lordship had given him a letter of recommendation. I think that if he was still living, he would be glad to know the fate that has befallen his old friend. So then, if you had the noble goodness to tell him of that, if you can, I will remember always with gratitude your charity towards me.

There is the task I am endeavoring to impose on you; you will find me certainly impudent, but I think that you will praise at least my purpose. You will excuse my English composition because I have forgotten my native tongue in Canada.

It is with the greatest respect that I am your fellow countryman and your son in Jesus Christ.

Robert Walsh.

[Archives du Séminaire de Nicolet, F091/B1/5/2 & F091/B1/5/3, transcribed and translated by Jason King]

There is no evidence that Robert Walsh ever received a reply to his letter. He did, however, embark on his own voyage to Ireland in 1872 to find his younger sister, but was sorely disappointed because nobody remembered his family or where they had lived. He returned to Quebec and died soon thereafter on January 31, 1873, at the age of 33. Although he was unsuccessful in finding his younger sister, it is entirely possible that she survived the famine and had children of her own, whose descendants might still be found in the Kilkenny area or elsewhere.

Robert G. Kearns, the Chairman of Ireland Park Foundation is actively seeking to trace the Irish descendants of Robert Walsh's family, and the living relations of other Famine emigrants who travelled to Canada or left family members behind in Ireland. Ireland Park Foundation is dedicated to celebrating and commemorating the Irish presence in Canada. It seeks to enrich the relationship between Canada and Ireland through the building of commemorative public spaces, funding historical research and hosting cultural events. As part of its mission, Ireland Park Foundation is seeking to trace the living relatives and descendants of Irish Famine emigrants, like members of Robert Walsh's family, whom he was unable to find on his own journey back to post-famine Ireland. The stories of their endurance and self-reliance in surviving the Famine, as well as the benevolence of those Canadians who helped them, attest to a legacy of Irish resilience in Canada that Ireland Park Foundation commemorates.

If you have any information, please contact: http://www.irelandparkfoundation.com/contact/