Irish Famine Orphan siblings Patrick (12) and Thomas Quinn(6) and Daniel (12) and Catherine Tighe (9)

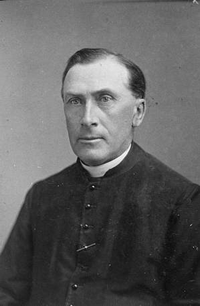

"Remember your soul and your liberty", declared James Quinn, a forty-five year old Irish emigrant from Lissonuffy on the Denis Mahon estate in Co. Roscommon, to his two young sons Patrick (12) and Thomas (6), as he lay dying in the quarantine station on Grosse Isle, Quebec, in late August, 1847. Sixty-four years later, his son, the Abbé Thomas Quinn, stood before the First Congress of the French Language in North America, on June 25th, 1912, to express his gratitude to the people of French Canada for their "untiring charity", which enabled "my unfortunate parents…to sleep in peace with God, pardoning their enemies, and carrying with them the ineffable consolation of leaving their children in the care of French-Canadian priests".

At the 2014 National Famine Commemoration in Strokestown, Co. Roscommon, the Irish Taoiseach Enda Kenny echoed Thomas Quinn when he unveiled a glass wall memorial to the 1490 people who were forced to emigrate from the Mahon estate in 1847 on board some of the most notorious "coffin ships". The estate of Strokestown Park House from which they fled is now the site of the Irish National Famine Museum.

Like Quinn, Kenny paid tribute to Quebec's "priests and nuns… and especially… the French-Canadian Sisters of Charity… the Grey Nuns… and the quality of their mercy" for looking "after 800 children whose parents had died on board the emigrant ship". [Speech by the Taoiseach, Mr. Enda Kenny, T.D. at the National Famine Commemoration, Strokestown, Co. Roscommon, 11th May 2014].

The return of the descendants of emigrant orphan Daniel Tighe from Quebec to Strokestown in July 2013, provided another occasion for the commemoration of the Famine exodus, as a flagship event of 'The Gathering'. It was filmed by RTE's Nationwide:

Two days later the Virginius, which also carried assisted emigrants from the Mahon Estate, arrived at Grosse Isle with an even higher mortality rate of over fifty percent or 267 of the 467 steerage passengers on board. Even by the standards of 1847, the conditions on board the Naomi and Virginius were horrific and only obliquely recalled by the Quinn and Tighe children and their descendants in their subsequent recollections. In the words of Daniel's grandson Léo Tye, who was interviewed by Marianna O'Gallagher and met with Jim Callery, founder of the Irish National Famine Museum at Strokestown:

In 1847, Mary, widow of Bernard Tighe, left Ireland with her five children and her younger brother… The voyage was a long nightmare of eight weeks. Drinking water ran low and food was reduced to one meal a day. Comfort and hygiene were non-existent. Typhus broke out on board, and the ship was ordered to stop at Grosse Île. Of Mary Tighe's family, only two children survived: Daniel (12), and Catherine (9). When the children left the ship, they never saw the other family members again, nor did they have any word about them. [Marianna O'Gallagher, 'The Orphans of Grosse Île: Canada and the adoption of Irish Famine Orphans, 1847-48', in Patrick O'Sullivan (ed), The Irish World Wide: The Meaning of the Famine, (5 vols, London and Washington, 1997) iv, 90]

Likewise, Thomas Quinn's recollection of his famine voyage decades later was equally sketchy: 'In the designs of Providence, we were cast upon the shores of Grosse-Ile after a stormy passage of two months at sea. A malady,… – the famine fever – came to add its untold terrors to so much other suffering and misery', he declared at the French Language Congress in 1912.

In fact, both the Quinn and Tighe children were evacuated from the quarantine station at Grosse Isle in August and September of 1847 into the care of the Catholic Orphanage run by the 'Charitable Ladies of Quebec' and, after 1849, the Grey Nuns, who presided over their adoptions into French-Canadian and Irish Catholic families. As grandson Léo Tye recounts:

On 8 August 1847, Daniel and Catherine along with several other immigrants left Grosse Île on a sail boat which brought them to… the General Hospital [in Quebec] where they were very well treated. Then one morning, the pastor of Lotbinière, Father Edouard Faucher, came to get Daniel and Catherine and eleven other Irish children. He loaded them into his horse drawn 'express wagon' [and] during the long trek, held one of the smaller children on his knees. [Marianna O'Gallagher, 'The Orphans of Grosse Île', p. 91]

Léo Tye also recalls how his grandfather Daniel and his sister Catherine were adopted by the French-Canadian Coulomb family who decided to keep the children together after they 'cried so hard at the idea of being separated that they were inconsolable…. The Coulombs proved to be good parents to these two orphans', Léo Tye added. 'Upon the parents' death, Daniel inherited their good farm, which since then, has been handed on from father to son'.

Like the Tighe orphans, Patrick and Thomas Quinn were also escorted by clergy from Grosse Isle to Quebec and then adopted into a French-Canadian family. According to the Annals of Richmond County in Quebec's Eastern Townships:

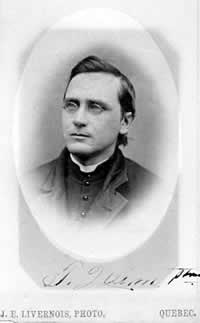

Previous to his appointment at Richmond Fr. [Luc] Trahan had worked at Grosse Isle Quarantine Station in 1847… [He] took under his protection two orphaned boys, Patrick and Thomas Quinn whose father James Quinn and mother, Margaret Lyons, of Strakestown, [sic] Co. Roscommon, Ireland, had died of the fever. Through his efforts, the two boys were adopted by a French-Canadian family named Bourque, at Nicolet. They completed their education at the Seminary at Nicolet and both entered the priesthood.

Father Patrick Quinn [the elder brother] succeeded his benefactor Fr. Trahan as Pastor at… Richmond [where he remained parish priest for 50 years until his retirement in 1914]. [Richmond County Historical Society, The Tread of Pioneers: Annals of Richmond County and Vicinity (2 vols, Richmond, Quebec, 1968), ii, 39]

The adoptions of the Quinn and Tighe famine orphan siblings into French-Canadian families thus symbolizes a wider story of social acceptance and the upward mobility of model immigrants who became thoroughly integrated into the agrarian and ecclesiastical institutions of Quebec's host society. As parish priests and proprietors of the family farm, they left behind the famine afflicted Mahon Estate and typhus infested Naomi's steerage and Grosse Isle fever sheds to start new lives ascending social ladders they could never have gained a foothold on in Ireland.

Perhaps the most poignant expression of Irish gratitude came from the Famine orphan Thomas Quinn himself, who 'was ever grateful to the French Canadian people and [for whom] it was an honor… to proclaim it publicly when the occasion arose'. [Second Parish Priest of Richmond 1864-1914', n.d., Richmond County Historical Society, Melbourne, Quebec, Hayes Papers, 03-G-F- 26.62]. According to the unpublished Hayes papers held by the Richmond County Historical Society,

Father Thomas Quinn, often related with emotion how, before leaving Grosse Isle, the admirable ecclesiastic who cared for his parents led him to the bedside of his father, who, when he recognized them exclaimed with his dying breath the old Irish slogan: – 'Remember your Soul and Liberty'. The incident remained deeply graven in his memory.

Indeed, Quinn equated his paternal injunction of remembrance with a pledge to preserve not only his French-Canadian parishioners' Catholic faith but also their cultural identity.

As they rose through the ranks of the clergy, the Quinn brothers endeavored to create institutions that would bring together their French and Irish parishioners. The most important of these was the St. Patrick's Society of Richmond, Quebec, founded by Patrick Quinn in 1877. His legacy of institution building was inspired by his father's injunction to safeguard the souls and the liberty of his French-Canadian and Irish parishioners.

More broadly, the remembrance of Irish famine orphans in Quebec tended to be evoked in a spirit of French and Irish fraternal association, especially to alleviate tension when relations between them became increasingly fraught in the latter nineteenth century. By the early twentieth century, their sense of rivalry had escalated following the controversy surrounding Regulation 17 in Ontario which restricted the teaching of French in Ontario's Catholic schools, an imposition widely supported by the province's Irish clergy. Shortly before Regulation 17 was implemented, the First Congress of the French Language in Canada was held in Quebec City on June 25, 1912. Its speakers included former Canadian Prime Minister, Wilfred Laurier, Quebec intellectual and founding editor of Le Devoir, Henri Bourassa, and Irish famine orphan Thomas Quinn.

As an Irish famine orphan who was no less a member of Quebec's French-speaking clergy, Father Quinn struggled to reconcile his Irish ancestry with his pastoral duties as he addressed the First Congress of the French Language in 1912. He took it upon himself to denounce the 'cruel irony' and 'deplorable contradiction' that put him in a position of seemingly having to choose between the land of his birth and that of his adoption. However, he left his audience in no doubt about where his loyalty belonged.

Of his Irish compatriots in Canada, he asked why after having suffered oppression they "want to be oppressive in turn? And that in circumstances marked by the blackest and most revolting ingratitude?" In the face of such ingratitude, Father Quinn sought to placate his audience by paying tribute to the generosity of the French-Canadian clergy and family that adopted him six decades years earlier.

As he stood before the First Congress of the French Language in Canada, Father Thomas Quinn delivered a speech entitled "Une Voix d'Irlande" – "A Voice of Ireland". Speaking in French, he declared:

I do not belong by birth to the French family. The language of my childhood is a foreign language, and if I am afforded the great honor to speak before this patriotic gathering, then it is as an adopted child and son of Ireland.

But, ladies and gentlemen, the adoption was a complete success and I claim my place at the paternal table. The French language, it is mine as it is yours. Those dedicated priests spoke the language through which my father could die in peace in the land of exile, forgiving his persecutors in Ireland! My adoptive parents spoke that language when they took me in at five years of age; they spoke it when they instructed me in my youth! It is still the tongue of old, and it is in this language that I am here today to recognize the people of French-Canada who adopted and took in an Irish son…

French Canadians, you can proudly claim the right to speak your language. It is a right for which you have made sacrifices!

This right so long disputed, and sanctioned by royal authority itself, seemed now safe from hostile forces.

But after coming out victorious from this long struggle, the French-Canadian race had to contend with something still more painful, the ingratitude and treachery of ostensible friends. And I come, ladies and gentlemen, to this troubling question of the relationship between my original and my adopted race.

Cruel irony! Deplorable contradiction! Both races seem to live next to one another, in this land of America, their ancestors were in Europe, inseparable allies. Cremona, Fontenoy, Laugfeld, you have witnessed the warriors of the Emerald Isle who amazed you with their bravery and heroism, and ensured that France had brilliant victories….

Why, in changing countries, do these paragons of justice and law break their alliance with the old sons of France? Why, above all, does that noble patient, chivalrous people, which has suffered from oppression, want to be oppressive to turn? And that in circumstances marked by the blackest and most revolting ingratitude?

I spoke of evil and oppression. What people underwent the weight of evil and oppression as much as did those in Ireland? It is not my intention, on this occasion, to recall its history of bloodshed which is so ingrained in the Irish story.

Allow me, however, ladies and gentlemen, to describe an incident in which I was involved, an incident in which I was myself an actor and victim.

It was in 1847. A famine, even worse than the one which had preceded it, threatened the Irish people with total extinction. The most astonishing part of the awful spectacle was, not to see the people die, but to see them live through such great distress.

During the course of three years, more than four million unfortunates, miraculously escaping death, took the road of exile from their native country. Like walking skeletons they went, in tears, seeking hospitality from more favored lands.

In the designs of Providence, we were cast upon the shores of Grosse-Ile after a stormy passage of two months at sea. A malady, known nowhere else to science, – the famine fever – came to add its untold terrors to so much other suffering and misery.

Canada, however, had foreseen the advent of these people and had acknowledged them as brothers in Christ. Stirred with compassion, French-Canadian priests, braving the epidemic, contended for the glory of rushing to their relief. French-Canadian clergymen, be eternally blessed for your heroism! You, above all, who fell victims to your devotedness! Glorious martyrs of charity, enjoy forever in glory the reward you so justly merit!

Thanks to your untiring charity, my unfortunate parents were able to sleep their last sleep in peace with God, pardoning their enemies, and carrying with them to the grave the ineffable consolation of leaving their children in the care of French-Canadian priests.

I still remember one of these admirable clergymen who led us to the bedside of my dying father. As he saw us, my father with his failing voice repeated the old Irish adage, "Remember your soul and your liberty".

Sixty-six years have passed since then, but my soul belongs to the French-Canadian people, and my spirit jealously guards their rights and freedoms.

If the episode I just recounted was not enough to instill a love of French-Canadians, there was another incident from my youth that would forever determine my preference for my country of adoption.

My adoptive parents to allow me to retain my mother tongue enrolled me in an English school, run by two old women, who were imbued with a sense of narrow bigotry. One day when the Blessed Sacrament passed in the street, led by a priest, I wanted to kneel, following the Catholic custom. My mistress reacted violently with an expression I will not repeat. I was forced to obey her, but never returned to the school. My education in English was over. It was not the language of my soul or my freedom!

The people of French-Canadian, too, were once abandoned by their mother country, and so they became orphaned. They had imposed on them a foreign language, unknown, and said: "It is not the language of our soul or our freedom!" After long and perseverant efforts, they finally obtained the privilege to speak French on an equal basis with English. But even where it was strongest, they never attempted to impose on others who lived near them their ideas and language. They wanted their freedom, but never sought to restrict the freedom of others. This is my ideal! And that is why these people have my affections and my preferences!

Dear descendants, God thank you, for your fathers cared for those starving and shivering with fever, and you are now seeking the right to speak your language, in the name and under the guise of religion, not to have imposed on you a foreign idiom!

I regret them deeply, but these attacks will succeed only in strengthening your national feeling and love of your mother tongue.

And if a man who is highly placed and venerable dares to speak out against the French in the preaching of the Gospel, there will always be some eloquent patriot to embody in himself the claims of his race, with a noble and respectful firmness.

Your language has been entrusted with a glorious mission and not a bankrupt one…

This right all must recognize, and my countrymen first. The Irishman is by nature a generous soul.

Just as O'Connell, defending his unhappy country, crushed by oppression unnamed, still found the time and means to claim religious freedom for his co-religionists in England and Scotland, who had been banished from these lands for three centuries, I recognize in his words the voice of Ireland, because he spreads the word of justice and freedom.

Ireland, real as God made it, by the ministries of Patrick, the Columbans and their successors, deserves and will always have my admiration and love. From it and not a bastard Ireland that is disfigured by unhealthy contact I proclaim myself a proud and devoted son.

Ladies and gentlemen, in this celebration of speaking French, I will, I believe, be the faithful interpreter of the feelings of us all, in expressing the wish and hope to see an end soon to the unfortunate and disastrous divisions between us. In this hospitable land of Canada, there must be a place in the sun for all races, for all languages, without any group seeking to stifle or limit the rights of another.

The Irish and French-Canadian races, both of them Catholic, are walking hand in hand towards the same ideal: the extension of Christ's kingdom, what a wonderful sight it would give the world! And is religious progress the principle of their union?

Is this a dream or a mirage that lies before me? The future will tell.

In any event, I, as the child of a courageous mother, who struggled against her oppressors, bit by bit, to preserve his heritage and freedom, tell my French-Canadian friends and my benefactors: struggle without fear, like O'Connell and Redmond, because your cause is right and just and cannot perish.

[Thomas Quinn, 'Une Voix d'Irlande', in Premier Congrès de La Langue Français au Canada. Québec 24-30 Juin 1912 (Québec, 1913), pp. 227-232. Translated by Jason King].

Nobody listening to Father Quinn that day could have been in any doubt that his personal experience of linguistic and religious suppression was being imposed on a much larger scale on French children in Ontario by his fellow Irish clergy. Not only did Father Quinn proclaim his solidarity with his French-speaking brethren, however, he also likened their condition to his own. "The people of French Canada, too, were once abandoned by their mother country, and so they became an orphan", he declared, alluding to the British Conquest of Quebec. "They had imposed on them a foreign language, unknown, and said: "It is not the language of our soul or our freedom"'.

In his remembrance of his father's dying utterance, Quinn identified his French parishioners' vulnerability with his own. Just as he was taken in as a helpless orphan by the French-Canadian people, he would now champion their linguistic and religious freedom in turn. Just as his adoptive parents had taught him "to preserve his heritage and freedom", Father Quinn implored his audience to "struggle without fear, like O'Connell and Redmond, because your cause is right and just and like theirs cannot perish".

He thus equated Ireland's demand for Home Rule with the French-Canadian struggle for "la survivance". Father Quinn's reclamation of Irish ancestry was inspired by feelings of solidarity with his French-Canadian more than Irish parishioners. He spoke on behalf of his French-Canadian parishioners to give expression to the language of their soul and their freedom which was threatened by his native tongue. In traveling from Famine Ireland to Quebec, he found his Irish voice in French Canada.

The glass wall memorial unveiled by Taoiseach Enda Kenny at the Irish National Famine Museum in Strokestown not only commemorates the 1490 people like the Quinns and Tighes who were forced to emigrate from Denis Mahon's estate in 1847; it also marks a campaign to trace them and their descendants. There can be little doubt that the Quinn brothers, who left extensive archival records, created much of the cultural and built-up physical heritage in towns like Nicolet and Richmond, Quebec, and who figure proudly in the pantheon of French-Canadian nationalism, should feature prominently in the public memory and help put a face on the 1490. Likewise, the return of the descendants of famine orphan Daniel Tighe during 'the Gathering' festivities in Strokestown in 2013 also attests to the increasing interest in the remembrance of the famine migration.

Richard Tye, however, was not the first descendant of the 1490 famine cohort to make an emotional return journey to his homeland. Indeed, in 1887, Father Patrick Quinn himself "was able to realize the cherished dream of his life and to see once again his native land of Ireland, whence he had gone many years before under such trying conditions". According to the Hayes papers, "in Ireland it was his good fortune to find members of his family still living, in the persons of several nieces and nephews. One of them, Miss Mary Quinn accompanied him on his return to Canada and remained with him until his death". ['Second Parish Priest of Richmond 1864-1914', n.d., Richmond County Historical Society, Melbourne, Quebec, Hayes Papers, 03-G-F- 26.62.].

![Jacket once belonging to [Thomas] Quinn, a six year old Irish Famine orphan', 1847, Textile, Archives du Séminaire de Nicolet, 1990.21.226.1-32]](/images/min/img-jacket-quinn.jpeg)

As a material cultural artifact, its miniature size confronts viewers with a palpable reminder of the absolute vulnerability of the Irish orphaned children like the Tighe and Quinn siblings who arrived in Quebec, and the great distance they travelled not only geographically but also socially to start new lives overseas. Together these cultural, familial, institutional, and memorial artifacts and traces comprise much of the legacy of the 1490 tenants and orphaned children who were forced to emigrate from the Mahon estate in Strokestown and from across Ireland to Quebec in 1847. The recovery of their legacy has now begun in earnest.