Clergy

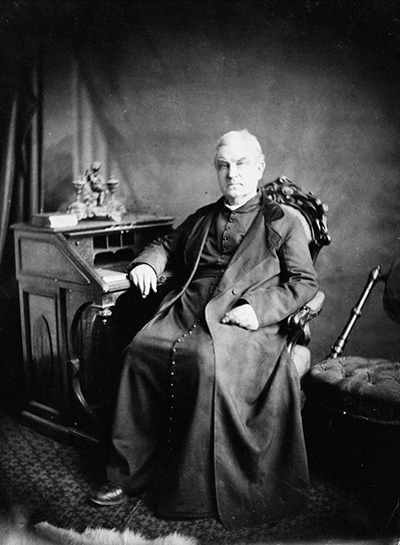

The cleric in the backround of Théophile Hamel's painting Le Typhus (1847-1848) is Montreal's Bishop Ignace Bourget, who had commissioned it after he recovered from typhus fever himself. As recounted in the "The Typhus of 1847" annal, the painting represents "the typhus seeking to enter the city but stopped at the gate by the [the Virgin Mary's] strong protection" (Le Typhus de 1847 / The Typhus of 1847 Virtual Archive, p. 68).

The cleric in the backround of Théophile Hamel's painting Le Typhus (1847-1848) is Montreal's Bishop Ignace Bourget, who had commissioned it after he recovered from typhus fever himself. As recounted in the "The Typhus of 1847" annal, the painting represents "the typhus seeking to enter the city but stopped at the gate by the [the Virgin Mary's] strong protection" (Le Typhus de 1847 / The Typhus of 1847 Virtual Archive, p. 68).

Some members of Montreal's Irish community have claimed, however, that the priest depicted in Le Typhus is actually Father John Jackson Richards, the first priest to serve the city's English speaking Irish Catholic community from the year 1817 in the same church, Bonsecours, in which the painting was installed. Father Richards perished in the fever sheds while caring for Irish Famine emigrants on July 23rd, 1847. His death is recounted in the "The Typhus of 1847" annal as follows:

A new mortality came to fill these two houses with pain. The venerated M. JOHN JACKSON RICHARD succumbed as well, at the age of SIXTY-EIGHT (68), an admirable devotion he displayed towards his unfortunate Irish brothers. It has been said, that it was him that welcomed them during the first night of their arrival; it was also him who persuaded the emigration intendant to ask the Sisters of Charity for their aid in caring for the sick. It was him again who interested himself with so much tenderness in the poor little orphans at the SHEDS; he procured them shelters, had them given clothes and prepared them for bed. (Le Typhus de 1847 / The Typhus of 1847 Virtual Archive, p. 43)

In 1866, John Francis Maguire, the founder and editor of the Cork Examiner, traveled to Quebec City and Montreal during a tour of North America which he recorded in his book The Irish in America (1868). After meeting with members of the Irish communities in both cities, he wrote one of the most detailed and evocative accounts of the impact of the Famine Irish in Canada based on eye-witness testimonials. He described the death of Father Richards as follows:

Among the priests who fell a sacrifice to their duty in the fever-sheds of Montreal was Father Richards, a venerable man, long past the time of active service. A convert from Methodism in early life, he had specially devoted his services to the Irish, then but a very small proportion of the population; and now, when the cry of distress from the same race was heard, the good old man could not be restrained from ministering to their wants. Not only did he mainly provide for the safety of the hundreds of orphan children, whom the death of their parents had left to the mercy of the charitable, but, in spite of his great age, he laboured in the sheds with a zeal which could not be excelled.

'Father Richards wants fresh straw for the beds,' said the messenger to the mayor.

'Certainly, he shall have it: I wish it was gold, for his sake,' replied the mayor.

A few days after both Protestant mayor and Catholic priest 'had gone where straw and gold are of equal value,' wrote the Sister already mentioned. Both had died martyrs of charity.

Only a few days before Father Richards was seized with his fatal illness he preached on Sunday in St. Patrick's, and none who heard him on that occasion could forget the venerable appearance and impressive words of that noble servant of God. Addressing a hushed and sorrow-stricken audience, as the tears rolled down his aged cheeks, he thus spoke of the sufferings and the faith of the Irish:–

'Oh, my beloved brethren, grieve not, I beseech you, for the sufferings and death of so many of your race, perchance your kindred, who have fallen, and are still to fall, victims to this fearful pestilence. Their patience, their faith, have edified all whose privilege it was to witness it. Their faith, their resignation to the will of God under such unprecedented misery, is something so extraordinary that, to realise it, it requires to be seen. Oh, my brethren, grieve not for them; they did but pass from earth to the glory of heaven. True, they were cast in heaps into the earth, their place of sepulture marked by no name or epitaph; but I tell you, my clearly beloved brethren, that from their ashes the faith will spring up along the St. Lawrence, for they died martyrs, as they lived confessors, to the faith.'

The whole city, Protestant and Catholic, mourned the death of this fine old man, one of the most illustrious, victims of the scourge in Montreal.

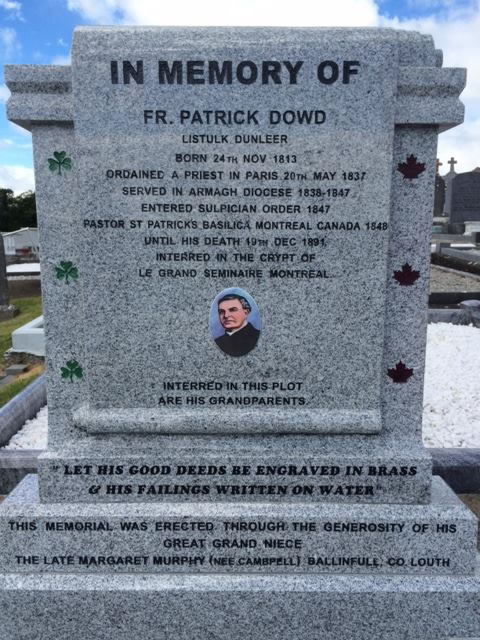

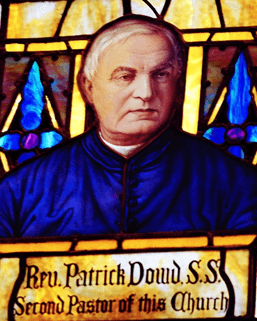

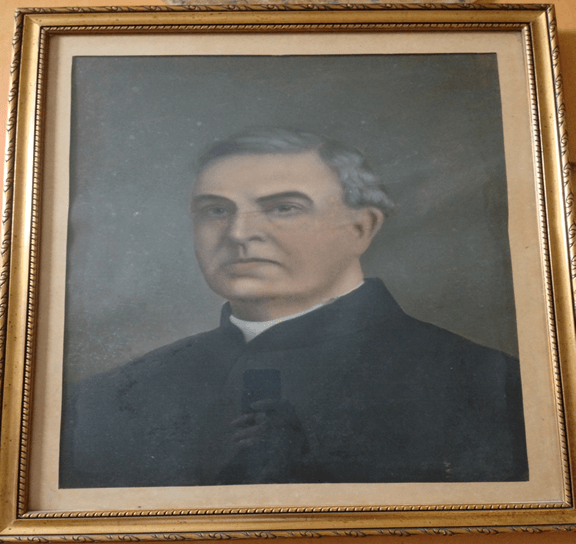

Despite the influence of Father Richards, however, the priest most closely associated with Montreal's Irish Catholic community and the care of Irish Famine emigrants was Father Patrick Dowd (1813-1891), originally from Dunleer, County Louth. During the summer of 1847, Father Dowd had also cared for famine victims in Drogheda and then he moved the following year to Montreal, where he worked tirelessly with the Grey Nuns to tend to the needs of typhus stricken Irish emigrants in the city's fever sheds, and to provide homes for widows and orphans. His story is recounted in this Digital Irish Famine Archive, especially "The Foundation of St. Patrick's Orphan Asylum".

St. Patrick's Basilica, Montreal.

Patrick Dowd was born in Dunleer in 1813, educated in the Junior Seminary in Newry and then the Irish College in Paris where he was ordained in 1837, after which he was assigned to the Parish Ministry in Drogheda. Between 1840 and 1843, he served at the seminary in Armagh, before returning to Drogheda until 1847. There are fewer archival records of Father Dowd's activities in Ireland then can be found in Canada, but biographical sketches indicate that before his departure he worked closely with Archbishop Crolly and moved frequently between Counties Armagh and Louth during the 1840s. According to the Golden Jubilee of St. Patrick's Orphan Asylum. The Works of Father Dowd, which was published in Montreal (1902), in 1842 Father Dowd was:

promoted to the curacy of Drogheda, under His Grace the Most Rev. Doctor Crolly, Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of all Ireland. After a short time, Father Dowd was transferred to the Rectorship of the Diocesan Seminary at Armagh, where he taught for two years. His next mission was to the curacy of Cullyhana, (Lower Cragan). This was one of the most trying positions. We find in the memo before us the following: "The wild inhabitants, of this wilder district, greeted the new curate with a smile, supposing him but little suited to the locality, and hardly equal to the toiling life his duties in this place would exact. But their preconceived notions soon changed, when, stick in hand, they saw him steadily pursue his way, through bog and fen, leaving many a deeply indented foot-print in the soil, as marks of his ardour and zeal." Three months later he was recalled to the curacy of Drogheda by... Doctor Crolly... What a contrast! The wretched residence in a poverty-stricken district he now exchanged, for the carpeted floors of the Primatial palace. There he was found by the Rev. Mr. Quibilier who, after many supplications to the Primate, finally, obtained leave for him to join the order of the Sulpicians. In August 1847 he bade adieu to all he held dear, and... he left the Bishop he loved, the Bishop who had stated to Rev. Mr. Quibilier in one of his conferences, "In asking for such a man, you ask for my own heart."

This biographical sketch attests to Father Dowd's extraordinary adaptability, his sensitivity to the needs of his parishioners, and indeed his tenacity in the face of obstacles and opposition. His temperament was shaped by his upbringing in the borderlands of County Louth, and he felt equally at home in Dunleer, Drogheda and Newry, Leinster and Ulster, "the carpeted floors of the Primatial palace" in Armagh and the wilderness of Cullyhana, the Irish College in Paris and then the fever sheds of Montreal.

Moreover, at the height of the Famine in 1847, Father Dowd left Ireland for France and Montreal, where he remained for over forty years until his death in 1891. From the moment of his arrival in Montreal in June of 1848, he became one of the most influential figures in the city's Irish community, and he almost singlehandedly created all of its Irish Catholic benevolent and social institutions, such as St. Patrick's Orphan Asylum in 1851, and St. Bridget's Home for the old and infirm (1865), which were first established to provide care for Famine migrants. Indeed, Father Dowd is renowned for being so devoted to his Irish Catholic congregation in Montreal that he refused three times to be appointed a Bishop in Toronto and Kingston so that he could remain with his flock. Although his legacy is perhaps better known in Montreal than in Ireland, Father Dowd had strong local roots in Dunleer and Drogheda as well as Armagh, where he first discovered the art of institution building during the pre-Famine and Famine periods. It was the lessons he learned as an administrator under Archbishop Crolly that he put into practice in creating the social infrastructure for Montreal's Irish Catholic population.

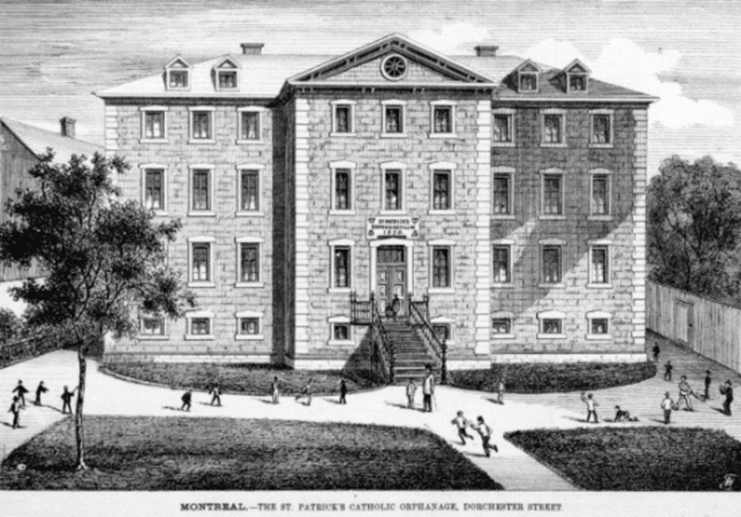

As a priest who ministered to the Famine Irish on both sides of the Atlantic, Father Dowd's legacy appears most discernible in these social institutions he established, especially St. Patrick's Orphanage, which in the later nineteenth century became a monument to him and the resilience of the Irish community that he served. The widespread adoption of Irish orphans into French-Canadian families during the Famine migration of 1847-48 has been extensively commemorated on both sides of the Atlantic. This predominant memory of French-Canadian generosity, however, also overshadows Father Dowd's legacy of institution building in Montreal, which ultimately provided homes for many more Irish children than were ever taken in by Quebec families. In the year before his arrival in Montreal, hundreds of the Irish orphans were still scattered between hastily improvised fever sheds and makeshift shelters around the city. They were also in the care of the female religious congregations, such as the Grey Nuns, the Sisters of Providence, and the Sisters of St. Joseph who took turns in sheltering and tending to famine migrants since their massive influx in June of 1847.

According to the annal:

When she found herself surrounded by the orphans who absorbed her teachings like thirsty earth absorbs the dew, she thought of her little Rose: 'If I had her here with me, she said, I would teach her with all the others.' With this weighing on her mind, one March evening, she attended a Lenten prayer service or a benediction of the Holy Sacrament in St Patrick's church. In the silence of the ceremony, she was disturbed from her contemplation by the sound of a marble rolling on the floor which came to rest in the folds of her clothes. She had barely raised her eyes when she saw a little girl aged three or four running to collect it. 'Is this not my little Rose', she said trembling with emotion. Indeed, it was this child who she mourned and thought she had lost forever, now returned to her at this moment by our Lord, and by instinct, she reached out. However, her adoptive mother who had missed nothing of what happened, intervened and protested. Before the ceremony had even finished both women went to the sacristy to submit the case to Father Dowd. He did not delay in resolving the issue, and that very evening, Madame Brown triumphed, coming back to the refuge with little Rose.

This incident of Irish family reunification attests to the broader role that Fr. Dowd played in bringing Montreal's Irish community together. Indeed, what the annals of the Grey Nuns do not fully convey is the extent to which he brokered between different sections of the city's Irish Catholic population to resolve disputes and raise funds for his institution building projects.

Not only did Father Dowd reunite Irish orphans with their parents in Montreal, but he also sought to restore Irish children to their families back in Ireland whenever it was possible. Twenty years after his arrival in Montreal, John Francis Maguire, the founder and editor of the Cork Examiner, visited and stayed with Father Dowd in 1866 which he recorded in his book entitled The Irish in America. In his chapter entitled "The Irish Exodus" Maguire wrote about how "in some, but rare instances, visions of the past have haunted the memory of Irish orphans in their new homes". As he recounts:

One of these, a young girl who bore the name of her protectors, was possessed with a passionate longing to learn her real name, and to know something of her parents. A once familiar sound, which she somehow associated with her former name, floated through her brain, vague and in-distinct, but ever present. The longing to ascertain who she was, and whether either of her parents was still living, grew into an absorbing passion, which preyed upon her health. She would frequently write what expressed her recollection of the name she had once borne, and which she thought she had been called in her infancy by those who loved her. The desire to clear up the doubt becoming at length uncontrollable, she implored the cure of her parish to institute inquiries on her behalf. Written in French characters, nearly all resemblance to the supposed name was lost; but through the aid of inquiries set on foot by Father Dowd, the Parish Priest of St. Patrick's, in Montreal, and guided by the faint indication afforded by what resembled a sound more than a surname, it was discovered that her mother had taken her out to America in 1847, and that her father had never quitted Ireland. A communication was at once established between father and child; and from that moment the girl began to recover her health, which had been nearly sacrificed to her passionate yearning.

As in the case of Suzanne Brown and her lost daughter Rose, Father Dowd played a key role in reuniting this disconsolate orphan with her father back in Ireland. As a French speaking Irish Catholic priest, he was able to mediate between the two languages of Montreal and carefully reconstruct her ancestry and origins from her confused "recollection of the name she had once borne". Indeed, Father Dowd's ability to trace her roots from such scant genealogical records as were "written in French characters, [when] nearly all resemblance to the supposed name was lost…. [and being] guided by the faint indication afforded by what resembled a sound more than a surname", attests to his familiarity with and sensitivity to both his host French-Canadian and native Irish cultures. Above all else, he was a great communicator who went to extraordinary lengths to provide comfort for the children in his care.

Both in Ireland and Montreal, Father Dowd's career was defined by his profound sense of concern for Irish widows and orphans as well as his practical endeavors to create institutions to support them. His records that are being digitized for this archive do not only serve to acknowledge his legacy but also provide an invaluable scholarly resource by making publicly accessible some of his letters for the first time. His correspondence reveals that Father Dowd remained in close contact with his family in Dunleer long after he had left Ireland behind. Shortly after his arrival in Montreal, Dowd wrote a letter to his father during the latter stages of the Famine on 25 October 1850: "I am sorry to see by the papers that the potatoes are damaged this year again," he notes. "Write to me very soon and let me know whether your part of the country has escaped as I perceive that the injury is not great".

Not only did Father Dowd inquire about his family's wellbeing, he also expressed concern about the large numbers of Irish orphans and widows who were arriving destitute in Montreal from Ireland's western seaboard. In his own words:

I have had a very large number of emigrants this year. They come out for the most part in good health, tho sufferings of a great number are truly afflicting to witness on their landing. Whole cargos of widows with small children and young females emptied out from poor houses in the south and west land here not knowing where to turn to – their young exposed to the worst of dangers from their exposed condition. The widows unable to work from the burden of their children. This is one of our greatest embarrassments in Montreal. Why send out a poor woman with three or four helpless children to lose herself and them in a strange land where she will have no neighbour or relative to pity or assist her? Hundreds of children are yearly in this country by the cruel – I would say barbarous policy of your landlords and Poor law Guardians.

Father Dowd certainly did not espouse the tenets of revolutionary Irish nationalists; but in his seething anger at the "cruel" and "barbarous policy" of "landlords and Poor law Guardians", he made common with them on the issue of suffering orphans and widows. His utter repudiation of neglectful landlord and Poor Law assisted emigration, which led to "whole cargos of widows and small children and young females [being] emptied out from poor houses in the south and west… not knowing where to turn", would provide the impetus for Father Dowd to create his own network of social institutions. In particular, he helped establish institutions like St. Patrick's orphanage to protect vulnerable children and young women from "the worst of dangers" of "their exposed condition". Indeed, less than a year after Father Dowd complained of "our greatest embarrassments in Montreal", St. Patrick's orphanage had opened its doors. It was his legacy to ensure that no Irish women or children would find themselves abandoned "in a strange land" with nowhere else to turn.

Not only did Father Dowd protest vehemently against the neglect of female and child emigrants when they were "emptied out from poor houses", he also corresponded with the Poor Law Guardians in Drogheda to ensure that assisted migration was carried out in a humane and orderly manner. On 24 September 1855 he wrote from the Montreal Seminary, in a letter reprinted in the Drogheda Argus, to acknowledge the arrival "in good health" of a group of young women from Drogheda whom he ensured were fed, found employment, and procured lodgings. While Father Dowd was happy to receive emigrants from his home in Drogheda who could be vouched for, he also warned that female migrants from other Poorhouses such as in Dublin continued to be neglected. As he cautioned:

They seldom change for the better by being transferred to a strange place – where they are under no restriction – and have no friend or neighbour to advise them: generally, such females fall into bad hands, and inflict much injury on the larger number of good females coming from Ireland. In Montreal, we suffered much, and still suffer, from a large importation of very badly conducted girls sent out last year from a union in the city of Dublin[, many of whom ended up in prison]. Nothing has ever occurred, more damaging to the character of our good Irish girls in this place.

Father Dowd's admonitions were received with the utmost seriousness by the Drogheda Guardians, who took the liberty of reprinting his letter when another emigration related controversy involving the philanthropist Vere Foster arose a year later, as reported in the Drogheda Argus (14 June, 1856). Indeed, they advised Vere Foster to emulate Father Dowd in being "prepared to protect" the emigrants who fell under his care. Once again, Father Dowd himself responded to this social problem by creating an institution, St. Bridget's, which provided a home not only for the aged and infirm, but also young women as well as a night refuge for the homeless. Like St. Patrick's orphanage, St. Bridget's home was also a monument to his legacy.

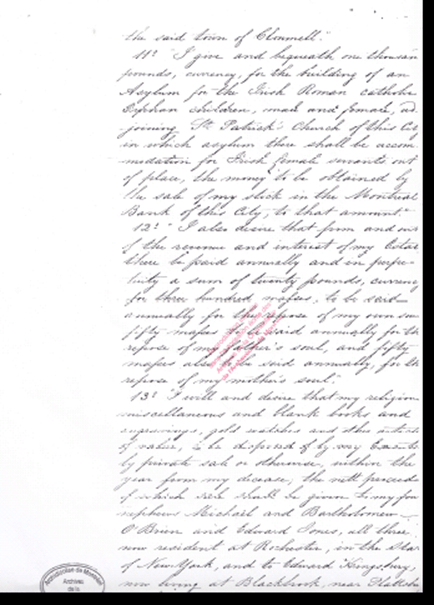

In establishing his legacy, Father Dowd ensured that the more affluent members of the Irish community provided charitable support for the most vulnerable. The single most important contributor to the establishment of St. Patrick's Orphanage was, in fact, a wealthy boarding-house keeper, moneylender, and silver broker originally from Clonmel named Bartholomew O'Brien, whom Father Dowd persuaded to bequeath "one thousand pounds, for the building of an Asylum for the Irish Roman Catholic orphan children... of this city" in his last will and testament in 1849. As a wealthy proprietor, Bartholomew O'Brien had little contact with the Famine emigrants himself, but his decision to endow the orphanage can be traced to the fact that Father Dowd was the executor of his will and present at his bedside as he lay dying. The orphanage when it was established not only became a monument to Father Dowd but also the Irish community that supported it. O'Brien's bequest was augmented with fundraising efforts to support the orphanage which created an institutional context for communal self-recognition. Charitable contributions to the Famine orphans served to bind all elements of the Irish community together and were a source of considerable pride.

In a broader sense, Father Dowd's programme of institution building can also be regarded as an extension of the ideals of the Catholic Revival or Devotional Revolution from an Irish to a Canadian context; but his emboldened style of leadership also brought him into conflict with French-Canadian ecclesiastical authorities, especially Montreal's Bishop Ignace Bourget. Furthermore, the institutions he created awakened a sense of historical consciousness in Montreal's Irish Catholic community that defined itself increasingly in terms of its insularity, religiosity, and self-sufficiency, especially when its institutions were perceived to be under threat.

In his later career, Father Dowd was celebrated as a man of peace, but paradoxically, he consolidated his clerical authority with single-minded and steadfast resistance whenever his influence was challenged. After he had been in Montreal for almost two decades, Father Dowd's control over his congregation appeared undermined both by the rise of Fenianism and escalating tension with Montreal's Bishop Ignace Bourget which came to a head in 1866. Although the Montreal Fenians did not succeed in launching a planned insurrection in 1866, they remained a formidable threat and were responsible for D'Arcy McGee's assassination in 1868, when it fell upon Father Dowd, in the company of two Grey Nuns, to inform his distraught wife of her husband's death. Their presence proved deeply disruptive for Irish Catholic communal harmony in dividing the more moderate clerical and political leadership of Father Dowd and Thomas D'Arcy McGee from their radical nationalist brethren, although after McGee's assassination the repression of Fenianism strengthened Father Dowd's hand in guiding his flock. In this context, he successfully conveyed the impression of an embattled Irish Catholic community that had to cleave to its own institutions to survive.

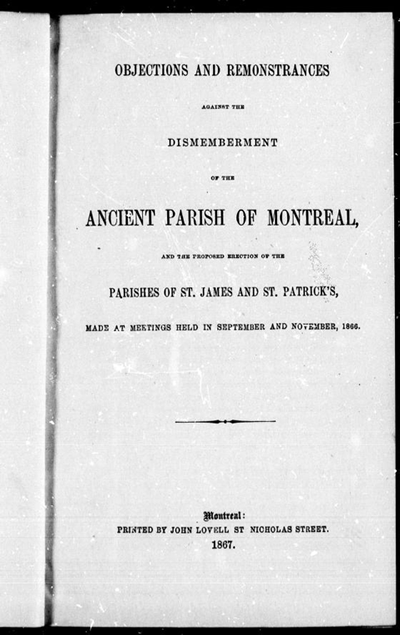

It was not only the Fenian scare, however, that consolidated Father Dowd's clerical authority over the Irish Catholic community in 1866. Even more important was Bishop Bourget's plan to subdivide the city's only parish into a number of smaller ones that was perceived to threaten the Irish clergy's control over St. Patrick's Church, the autonomy of its surrounding Irish institutions, and to fragment the city's Irish community at large. On November 8th, 1866, Father Dowd and D'Arcy McGee submitted a petition on behalf of his congregation to protest against Bourget's redistricting plan.

In the war of words that ensued between Father Dowd, D'Arcy McGee, and Bishop Bourget, the memory of the Famine orphans served to accentuate their differences. For example, in a pastoral letter read in St. Patrick's Church on the 23rd of November, 1866, Bishop Bourget all but accused the Irish of ingratitude, questioning if they had forgotten "when the ravages of the typhus left the children of your countrymen by hundreds, orphans on our shores, did we did not make an appeal to all our Diocese, to obtain for them other fathers and mothers, who as you know, reared them and cherished them as their own?" His insinuation that the Irish were forgetful and ungrateful for the sacrifice made by French-Canadians in caring for the Famine orphans two decades beforehand incensed Father Dowd and D'Arcy McGee, who took the unusual step of publishing a pamphlet entitled The Case of St. Patrick's Congregation that warned of the likelihood of "bloodshed" and "a domestic war between Irish and Canadian Catholics throughout the city" if the Bishop's plan was brought to fruition. These were extraordinary admonitions in the aftermath of the battle of Ridgeway the previous May when American based Fenians had tried unsuccessfully to invade Canada, and the Irish in general were under intense scrutiny for any incitement to violence. As stated in the pamphlet:

Your Lordship, referring to the sad events of 1847, is pleased to call us an 'unfortunate' people. In 1866 we are still 'unfortunate' – for your Lordship will not allow us to forget our sad destinies. The memory of all past afflictions must be kept fresh: and all the charities of which we have been the sad recipients, must be turned into an argument to force us to surrender, in silence, all the advantages of our present condition, which we owe to our own efforts,… and the generous sympathy of our immediate Pastors.

Thus, the Irish Catholic community in Montreal sought to emphasize its resilience and self-reliance in overcoming its "sad destiny" rather than its dependence on Bourget and French-Canadian co-religionists a generation beforehand. Thomas D'Arcy McGee and Father Dowd were determined to define themselves in terms of their advantageous "present condition" of prosperity and self-sufficiency instead of past afflictions. Their emphasis on "our own efforts" and "our immediate Pastors" refutes Bourget's insinuation that the Irish community survived only under his own pastoral care.

Then, in a second, even more strident pamphlet published openly by Father Dowd the following year, he declared St. Patrick's asylum to be a specifically Irish Catholic "institution which we, strangers here, have built out of the sweat of our brow to save the orphan children of our own race from vice and heresy." In his Objections and Remonstrances against the Dismemberment of the Ancient Parish of Montreal (1867), Father Dowd also insinuated that Bishop Bourget had become the equivalent of an Irish landlord, evicting members of Montreal's Irish community from the very institutions they had created less for reasons of ecclesiastical necessity than his own aggrandizement. "I cannot look upon the labor of years about to be destroyed," Dowd protested,

the monuments of charity raised and sustained by union of our whole people,… so long happily collected together under the shadow of their beloved St. Patrick's, about to be driven from his sanctuary, as not belonging to them; – thus bringing back to their memory that they were once before driven from their native land, as if it were not their home.

Far from being beholden to Bishop Bourget, Father Dowd now perceived him as complicit in Irish persecution. He also appealed, however, to Bourget's self-image as a paterfamilias "to whom the faithful children of St. Patrick always looked as a second father… not to inflict upon them the cruel blow of a second dispersion." In Father Dowd's view, the adoption of Famine orphans into French-Canadian families had been a prelude to the Irish community taking responsibility for their welfare through the establishment of St. Patrick's Orphanage. In his recollection, it was their plight that had provided an impetus for Irish institution building and communal self-realization that owed little to Bishop Bourget's ministrations. Ultimately, this parish redistricting controversy was resolved largely in the Irish community's favor, after Father Dowd and D'Arcy McGee appealed to the Vatican.

Accordingly, these ethno-religious struggles did not so much destabilize as consolidate Father Dowd's position as a leading figure in Montreal's Irish Catholic community. By 1866, Irish Catholics in the city had reached a moment of crisis that threatened to fragment their parishes and politically subdivide them along radical and constitutional nationalist lines, but the combined leadership of Father Dowd and D'Arcy McGee fended off the challenges mounted by the Fenians and then Bishop Bourget to hold the community together. After D'Arcy McGee's assassination, the disappearance of the Fenian threat, and the Vatican's resolution of the parish redistricting controversy, Father Dowd's communal and religious authority amongst the Irish in Montreal seemed increasingly secure.

By the later nineteenth century, the institutions Father Dowd created had become the cornerstone of Irish community life, and the orphans themselves he provided homes for were well integrated into its social activities. Visiting dignitaries were frequently brought to St. Patrick's Orphanage as a showpiece of Irish self-sufficiency, and the conspicuous role that the orphans played at community events was often observed. One such visitor was the Reverend Michael Buckley who travelled to Montreal while raising funds for the Cathedral of St. Mary and St. Anne, stayed with Father Dowd, and left a detailed impression of him in his book entitled Diary of a Tour in America. By Rev. M.B. Buckley, of Cork, Ireland. A Special Missionary in North America and Canada in 1870 and 1871 (1886).

In his Diary, M.B. Buckley attests to Father Dowd's generosity, his austere lifestyle, and his extraordinary work ethic.

As he recalls:

The Vicar-General, in the absence of the Bishop, who is in Rome, accorded us every privilege in his power to bestow, on condition, however, that we should receive the sanction of Father Dowd, the pastor of St Patrick's, and the chief of the Irish clergy in Montreal. We called on Father Dowd, who was even more gracious than the Vicar-General. He insisted on our leaving our hotel, and coming to live with him, as long as we remained in Montreal. I must here mention that all of the priests in Montreal are "Sulpicians," that is to say, clergy of the order of St. Sulpice, whose chief house is in Paris ; that they are established here since the foundation of the colony, and are owners in fee of almost all the property of the city. The clergy attached to each church live in community, and practice in a very special manner the virtue of hospitality to all their brethren in the ministry. We accordingly remove our baggage from one hotel and take up our quarters with Father Dowd, whom we find to be the type of all that is excellent in a priest… . The rules of the house are new to us. They rise at 4am, breakfast ad libitum, dine at 11:30- A.M., and sup at seven. Night prayer at 8, and after that bed. I agree to conform in all, save the early rising, but I learn that I am not bound to observe any part of the rule; but that I am perfectly free to act as I please; I do conform, however, through respect for the rule. (48)

To some I spoke the Irish language, and their delight was inconceivable. I may here remark that wherever I go I find the love of Ireland amongst the Irish to be the most intense feeling of their souls an all-absorbing passion, running like a silver thread through all their thoughts and emotions. They think forever of the old land, and sigh to behold it once more before they die. One man who drove us one day for an hour refused to take any payment. He was from Ireland, and we were two Irish priests, and that was enough for him!" What part of Ireland do you come from?" I asked." From Wicklow, sir; I am 32 years in the country." "And do you ever think of the old country?" "Think," he exclaimed, "Oh ! yes, sir, I do think of the old country, not so much by day as by night. In my dreams at night I see as distinctly as ever the lanes and alleys where I played when a boy. I fancy I am at home once more, but I wake and find that I am in Montreal, and am likely never to see my native land again." This dreaming of Ireland I found to be quite common; many people would give all they have in the world to get back again and live in Ireland steeped in poverty, rather than flourish wealthy in this strange land. And what is stranger still is, that amongst the young people, those love Ireland most who are born here of Irish parents. Their love is far more intense than the love of those who were born in Ireland. Philosophers must account for this: it appears to me to be a transmitted passion; they hear their parents constantly speak in terms of affection of the land of their birth. It is a land ever appealing to the sympathies of mankind a land that has suffered in the great and noble cause of religion. The imagination of the young heightens the colours of the picture and awakes all the fire of patriotic passion. Attached to St. Patrick's Church is St. Patrick's Orphanage. The boys have a band, and they play no airs but Irish. My ears were so constantly regaled with "Patrick's Day" and "The Sprig of Shillelagh" that I could hardly persuade myself that I was in Canada. Wherever I have gone I have been assured of this passion of the Irish whether Irish by birth or by descent this ardent love of their native land. (50-51)

Buckley's observation is not only about the retention of Irish ethnicity, but also that the orphans had become emblematic of communal identity. It was Father Dowd's achievement to make his congregation's most vulnerable children the centre of its attention and a source of local pride.

During his stay with Father Dowd in Montreal, Michael Buckley also became inadvertently involved in local politics and even a source of controversy. Like John Francis Maguire before him who had also stayed with Father Dowd in 1866, Buckley was struck by the fractious relations between the Irish and their French-Canadian neighbors, which he contrasted with their "healthful" and "holy rivalry" (81) to adopt Famine orphans twenty years beforehand. Indeed, he was dismayed by the "great antipathy" he witnessed between the French and Irish who seemed "embittered" towards one another "by national and political prejudices" (53).

Moreover, Buckley became a figure of opprobrium in Montreal's Protestant community when he inadvertently gave a speech on St. Patrick's Day that earned him the title of "Priestly Fenian". In fact, his first fund raising tour was so successful that the returned to Montreal in the spring of 1871 and then joined Father Dowd for the city's St. Patrick's Day Parade.

In his own words:

Hence under foot it is all wet and slushy, and walking without slipping is a matter of considerable difficulty. But I must walk; so I accompany Father Dowd and Father Singer, who march in their soutanes, and have bearskin caps on their heads. I slipped once or twice, and this puts me on my guard. I take Father Dowd's arm, and even so, get on with great trouble. It was the most difficult three miles I ever walked, and the dirtiest. Such a state as my clothes were in! Oh, holy St. Patrick, what did I ever do, that you should treat me so ? It was, nevertheless, a grand procession; the music was excellent, and in some places there were triumphal arches, with legends indicative of the blended feelings in the breast of religion and nationality. The spectators and gazers from windows enjoyed it as it passed along; but there was no shouting, no disorder. I asked if this procession gave offence to any party. No; on the contrary, all classes of people liked it, and would be greatly disappointed if it did not take place. I looked in vain for a drunken man. Strange to say, drunkenness is almost unknown in Montreal, and even in all Canada. This is very creditable to our people, and clearly proves that there is nothing in the national character incompatible with temperance. (233)

However, if the St. Patrick's procession passed on peacefully without giving offence to any party, then Father Buckley certainly did so when he delivered an address that same evening, in spite of himself. He recalled that it was "a difficult audience... [of] Catholics and Protestants, Irish and Canadians – some in favour of British Government, others opposed" in Montreal in which he "was loud on Irish religion and patriotism, and 'death' on English tyranny" (234). In his native Cork these nationalist flourishes and rhetorical formulations would not be particularly controversial, but in Montreal he had misread his audience. His oratory was perceived by many Protestants in the crowd to be incendiary and he had clearly not understood their sensitivities less than half a decade after the attempted Fenian invasion of Canada. M.B Buckley was subsequently denounced as a "reverent firebrand" and "priestly Fenian" (The Gazette, March 20, 1871; also see, "Irrepressible," The Gazette, March 29, 1871; and "Father Buckley's Lecture," Montreal Herald, March 29, 1871). The controversy led him to "conclude that the same feeling of bitterness on account of religion prevails here as it does in Ireland, and that unfortunately the Irish lack the blessing of cohesion which would make them a compact body, a phalanx of strength, and a terror to their enemies" (236-237).

In conclusion, unlike Father Dowd from the borderlands of County Louth, Michael Buckley did not understand the sensitivities and cultural, linguistic, and social fault-lines that both brought together and divided Montreal's Irish community in the mid nineteenth century. As a visitor to the city, he had misread the constant demarcation of ethnic, linguistic, and religious differences between Irish Catholics, British Protestants, and French Canadians which could occasion political and social tension when certain lines were crossed. The controversy surrounding his visit reminds us of the potential volatility inherent in Montreal's Irish community as well as the long established authority and skill exhibited by Father Dowd in guiding his flock and constantly reinforcing its sense of communal and national cohesion. It is true that Father Dowd could be no less critical of the "barbarous policy of Anglo-Irish landlords and Poor law Guardians" than Michael Buckley when confronted with the mistreatment of Irish orphans and widows, but he was also a deft communicator and shrewd negotiator who never misunderstood his congregation.

Ultimately, on occasions when we gather to commemorate the Famine Irish and those who cared for them, like Father Patrick Dowd and the Grey Nuns, we do not simply recall and recount the deeds of our ancestors. We also call upon them to hold us to account. It was in County Louth that Father Dowd first learned the art of institution building which he brought to fruition in the establishment of St. Patrick's orphanage and St. Bridget's home for the old and infirm in Montreal. He set an example to support the most vulnerable in his community, whether they are orphans or the elderly. As his memory has begun to fade in the land of his adoption, it is fitting that to acknowledge it in the place of his birth. In gathering together scattered famine orphans overseas into a permanent home; and supporting them by raising funds from the Irish community's more affluent members; and in placing those children at the very center of Irish communal life; Father Patrick Dowd has created a legacy and "monuments of charity" that should be honored and respected.